Yesterday I not only took a look at the Republican Primary standings, but I also went over why these standings are difficult to keep track of. The Republican standings, however, are a cakewalk compared to their Democratic counterparts. On the Democratic side, we have the same hurdles with which to contend, but the most obstructive one of all — unpledged delegates — is an ever bigger monstrosity. You know them better as superdelegates.

It’s hard to defend the concept of superdelegates, but like John Adams, Clarence Darrow, Atticus Finch, and other heroic American protectors of unpopular defendants, someone should try. Why not me?

Before that, let’s first establish exactly what they are, why they’re a thing, and what their ongoing purpose is. Then we’ll get to why they’re controversial and cause headaches when making the Democratic Primary standings.

What are they?

There will be an estimated 4,763 delegates at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, of which a majority (2,882) is needed to become the nominee. Of the 4,763 delegates, 712, or 15 percent, are “unpledged delegates,” better known on the Democratic side as superdelegates. “Unpledged” means that they are delegates that can vote any way they wish regardless of their home state’s primary results. The 712 superdelegates include the over 400 members of the Democratic National Committee; all the Democratic governors, U.S. Senate and House members; and “distinguished party leaders,” such as living former presidents, Congressional leaders, and Chairs of the National Committee.

Why do Democrats have them?

Ultimately, having a small chunk of delegates be these establishment leaders is the result of a compromise that evolved over decades. Brace yourselves for some recent political history.

This evolution began in the 1960s. The chaotic 1968 Democratic National Convention — which fit perfectly into a year that had racial unrest, anti-war demonstrations, riots in more than a hundred cities, and the assassinations of Dr. King and Robert Kennedy — was the last convention where centralized party elites held nearly all the control over the nomination process. Remember that for most of American history, both parties’ primaries hinged on the usually metaphorical but sometimes literal “smoke-filled rooms,” where powerful partisans essentially chose the nominees that made the most sense for their party (or their wallets) in any given election. In 1968, despite a majority of Democrats (who had already sunk President Johnson’s re-election chances to the point where he didn’t even run) wanting to nominate an anti-establishment, anti-war candidate (Eugene McCarthy was their candidate of choice), they ended up with Vice President Hubert Humphrey as their nominee, a man considerably inside the establishment.

After VP Humphrey lost to Republican Richard Nixon in the general election, party leaders received the backlash it deserved. Democratic voters wanted more of a say in the system, and the Democratic Party, trying to live up to its name, put together a commission that acquiesced. The party changed its rules and allowed voters to have almost total control over picking the nominee in the next election.

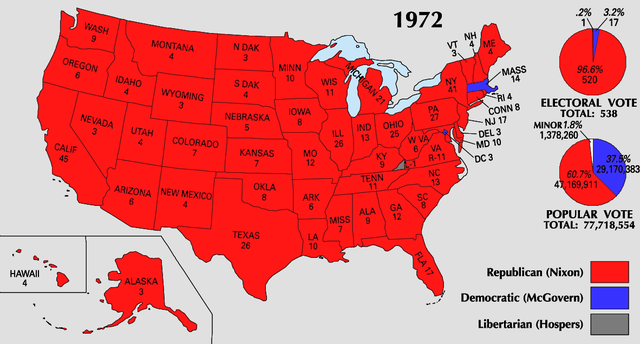

And then this happened:

In 1972, the Democrats, wanting the populist, leftist nominee (sound familiar?) denied to them four years earlier, nominated George McGovern, who went on to lose 49 states. (Twelve years later, the Democrats again nominated someone who took the rare tax-raising platform [again, sound familiar?], and he became the second person to lose 49 states.)

So that didn’t work. As a result, the Democrats once again reexamined their process. Within a decade, another commission determined that some delegates at the convention would be reserved for Congressional Democrats and state party leaders. Under the original plan, these delegates would have been about 30 percent of the total, but various pressures lowered that number to 14 percent by 1984. The number goes up and down each convention depending on the variables; it reached as high as 20 percent in 2008. This year it’s 15 percent.

So as undemocratic as it sounds, the current process is a lot more democratic than nearly all of nomination history before the last 50 years.

What are the arguments for keeping superdelegates today?

Good question. Not only are superdelegates a highly suspect and perhaps outdated practice, but superdelegates are also getting totally slammed by supporters of the internet’s favorite candidate. You won’t find many defenses of them… UNTIL NOW!

- Consider why the party did another course correction after ’72. Primaries for many elected positions can produce ideologically extreme candidates. It’s not just that only one party votes in most primaries; it’s that the most active and fundamentalist members of that party are more likely to vote. Moderates on both sides are rarely as motivated to attend rallies, donate money, make phone calls, and then show up to vote on primary day. Is it good for a party that it can easily nominate ideologues? Is it good for America if two of them are pitted against each other in a general election?

- Independents and other non-Democrats play a role in many caucuses and primaries. Eighteen states hold “open primaries,” where one’s party affiliation doesn’t matter; citizens can vote in whatever primary they want. For example, a Democrat can vote in the Republican Primary and vice versa. Another seven contests are mixed primaries (like New Hampshire) and allow unaffiliated voters to vote in a party’s primary. Democrats might feel skeptical of these outside voters picking their nominee. In fact, in 2008, Rush Limbaugh encouraged Republicans to vote for Hillary Clinton in the Democratic Primary in order to prolong their nomination process, a tactic he called “Operation Chaos.” Superdelegates diminish the influence of those outside forces.

- Similarly, if we take the case developing before our eyes, consider that part of the reason why superdelegates might support Clinton over Sanders is because Sanders has spent his entire career as something other than a Democrat, including being critical of them. Can you blame Democrats for holding a grudge and supporting the proud, decades-long Democrat? Superdelegates can help deny the nomination to a wolf in donkey’s clothing.

- Many say that these superdelegates have disproportionate voting power over the process, and it’s hard to disagree; thousands vote in a primary just to pick up one delegate for their candidate, while one superdelegate can negate that with one fell swoop of their own ballot. If we want to even the playing field, though, eliminating superdelegates would merely be the tip of the iceberg. Other party rules must face the same accusation. Is it fair, for example, that Iowa and New Hampshire have so much weight? Iowa is 91 percent white, New Hampshire 94 percent. The Democratic Party, however, is only 60 percent white. Why should a candidate who appeals to whites have a better chance merely because two tiny white states vote first? Do you know where this primary would be if South Carolina and Louisiana voted first? Clinton would be on her way to an easy 49 states and maybe Vermont, too. I don’t hear any Sanders supporters pointing this out, because in this case it’s the Sanders campaign that has taken advantage of the system. It’s Iowans and New Hampshirites who hold the most disproportionate influence over the process, not superdelegates. Superdelegates might even be a way for the party to keep things balanced until the primaries go national.

- We also mustn’t forget that the voters can still get their way despite the early declarations of the superdelegates. Superdelegates can change their minds at any point before the convention and even during it. Governor Dean (2004) and Senator Clinton (2008) also had big superdelegate leads early in the primary cycle, but John Kerry and Barack Obama started winning over the people, and eventually the superdelegates switched sides to push ahead the voters’ choice.

- Superdelegates can limit the power of the people, which, we cannot forget, was an aim of most of the founding fathers in case the “mob” got caught up in some sort of reactionary hysteria. Put another way: Democratic voters who are so critical of superdelegates should consider if they’d prefer that 15 percent of the Republican National Convention were unbound Republican party leaders that could help keep Donald Trump from the nomination and one November victory from the presidency.

How’d I do? Would Atticus be proud?

Why are they controversial?

This answer won’t need nearly as much support since it’s so obvious. It’s a far cry from the “one person, one vote” system many people like to think we have. It allows party leaders — usually rich, educated, establishment pols who know little of the plight of the average American — to attempt the undermining of the American people’s will. (But besides that it’s totally cool.)

Ever since Hillary Clinton was considered the inevitable 2016 Democratic nominee starting the day President Obama won re-election, she easily consolidated the support of the party. By August, she claimed 440 of them. CNN currently gives her a count of 436 superdelegates to Sanders’s 16. As a result, even though Sanders has more pledged delegates (36 to 32, according to CNN), here‘s how Google, citing the Associated Press, charts the race:

If you have a social media account, you already knew how Sanders supporters felt about this. Part of their anger stems from the undemocratic process of superdelegates, but part of it also stems from the (surprise, surprise) lack of responsibility from our media when showing these totals. Bar graphs like that might dissuade potential Sanders voters from joining the movement. It also doesn’t convey the nuances of superdelegates, including that they can all change their minds and many would in the unlikely event that Sanders earns the most votes and pledged delegates. Their support is not set in stone.

A similar problem is that the media too often discusses Iowa and New Hampshire results by total delegates instead of pledged delegates. Consider:

- Iowa gets 52 total delegates at the Democratic National Convention, but only 44 of them are pledged delegates. The other eight are superdelegates that just so happen to come from Iowa.

- New Hampshire gets 32 total delegates, but only 24 are pledged. Eight (coincidentally) are superdelegates that just so happen to come from New Hampshire.

When the Iowa and New Hampshire results are reported, the media should never break it down as 52 Iowa delegates and 32 New Hampshire delegates. It should only tell us about the 44 and 24, respectively, because that’s what the caucus and primary actually determined. The superdelegates are a totally different beast. It doesn’t matter where the superdelegates come from. It has nothing to do with the primaries and caucuses. They may have made up their minds months ago, and they might yet change their minds between now and the convention. I’d be shocked if they even stood with the pledged delegate riffraff on the convention floor. (That’s what skyboxes are for!) It’s misleading to say, “After crushing defeat, DNC quirk still gives Hillary more New Hampshire delegates than Sanders.”

That’s just simply not the way it happened. Reveal superdelegate numbers before, reveal them after, do a special on them, whatever. Just don’t say that Hillary Clinton matched Bernie Sanders in New Hampshire. He won it, and he won it big. To suggest otherwise is irresponsible and lazy journalism.

Anyway, whether we factor in these superdelegates or not greatly affects the standings. Do we not count them, since their votes are so pliable? Do we only count the ones from the states that have voted? Do we count all of them? You can see that in addition to the normal headaches discussed yesterday, the superdelegates are a superproblem in our calculations. Nevertheless, here are some attempts:

CNN (you’ll never guess if it’s using superdelegates):

- Clinton 468

- Sanders 52

Fox News (ditto):

- Clinton 394

- Sanders 44

Green Papers “Soft Count” (Includes Iowa and New Hampshire superdelegates; projects Iowa based on delegate equivalents, but those are subject to change — see yesterday’s post)

- Clinton 44

- Sanders 36

Green Papers “Hard Count” (Does not count superdelegates; does not count the Iowa caucuses for reasons discussed yesterday. These are only bound delegates so far. If you ask me, these are the actual standings.)

- Sanders 15

- Clinton 9

[…] (Author’s note: for a far-too-detailed look at why delegate projections don’t speak with one voice, click here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] although these aren’t nearly as divergent as projections for the Democrats, whose annoying superdelegates really muddy the waters. This early in the process, we still see Republican estimates largely in […]

LikeLike

[…] Here are the states with their pledged, unpledged, and total delegates. (Some states will donate their unpledged delegates to the pledged total. Are you listening, Democrats??) […]

LikeLike

[…] Voting opened at 7 and will close at 7 tonight. We’ll immediately get a projection for Hillary Clinton, before then watching to see what her winning margin is. […]

LikeLike

[…] (Author’s note: for a far-too-detailed look at why delegate projections don’t speak with one voice, click here.) […]

LikeLike

[…] primary, today holds 865, or a bit more than one-fifth. (We also can’t forget about the 712 superdelegates, which makes it 4,763 possible delegates, but they have nothing to do with today. About 150 […]

LikeLike

[…] get over 50 percent of the vote and rack up major, major delegates. (Not to be confused with super, superdelegates.) If Cruz can crank his state-wide total and/or a bunch of district totals to over 50 percent, he […]

LikeLike

[…] Clinton 1074 (606 pledged + 468 superdelegates) […]

LikeLike

[…] a long campaign with lots of delegates ahead. Ignore any delegate standings that count superdelegates, which are totally pliable until the day of the election. The pledged delegate standings show a […]

LikeLike

[…] #1. Florida Primary — 214 pledged delegates (does not count 32 superdelegates) […]

LikeLike

[…] again, he doesn’t have to. Those delegate standings include superdelegates. I’m familiar with them, including their history, purpose, undemocratic nature, ability to switch sides, and misleading […]

LikeLike

[…] a great narrative), or the media inadvertently crowning her by saying she’s inevitable or irresponsibly baking in the superdelegate numbers when talking about delegate standings (which shows Clinton […]

LikeLike

[…] “The Democrats made a mistake getting rid of most of their superdelegates.” Man, remember superdelegates? They were the over 700 party insiders who made up about 15 percent of the delegates at the […]

LikeLike

[…] were the five largest pledged delegations (not counting “superdelegates“) at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, which sat 4,051 pledged […]

LikeLike

[…] past years, the infamous superdelegates of the party don’t get to vote on the first ballot. Only if no candidate wins on the first […]

LikeLike